Alerts Aren’t the Investigation: What Comes Next in Incident Response?

Ben Yemini

February 9, 2026

In a recent post, Alerts Aren’t the Investigation, we described a problem that shows up in nearly every on-call rotation: alerts fire quickly, but understanding arrives late. A page tells you something crossed a threshold. It does not tell you what behavior is unfolding, how signals relate, or where to start if you want to stop the damage.

That delay is the Page-to-Understanding Gap. It is the translation cost of turning a page into an explicit explanation of system behavior. This is why MTTR improvements plateau even in teams with mature alerting and observability.

Engineers feel this cost most acutely during incidents today, but it is also what prevents alerts from being usable inputs to automated response workflows.

What comes next is closing that gap. That means grounding alerts directly in system behavior and causal context, so investigation starts with understanding instead of translation.

The problem alerts create during investigation

When an alert fires, the first requirement is not diagnosis. It is orientation.

Engineers need to know what kind of behavior is happening, whether multiple alerts point to the same underlying issue, and where to focus first. Alerts do not answer those questions. They were never designed to.

Most alerting systems encode thresholds, burn rates, or proxy signals that usually correlate with impact. They reflect past incidents and operational heuristics, not real-time system behavior. That is why the same alert can represent very different failure modes, and why many different alerts can describe the same underlying degradation.

As a result, the first minutes of an incident are spent translating alert language into a mental model of the system. Engineers jump between dashboards, traces, and logs to figure out what the alert actually means right now. Slack fills with partial hypotheses. Context fragments before anyone agrees on what problem they are solving.

This translation work is the gap. It is where time is lost and coordination breaks down.

The missing bridge between alerts and understanding

Alerts do carry some intent. They are not random noise. Each alert exists because someone believed a certain condition mattered.

What has been missing is an explicit bridge between that alert intent and an explanation of system behavior that can drive consistent action. Without that bridge, alerts remain isolated signals. Engineers are left to do the mapping themselves under pressure.

Closing the Page-to-Understanding Gap requires making that mapping explicit. An alert needs to land inside an explanation, not start a scavenger hunt for one.

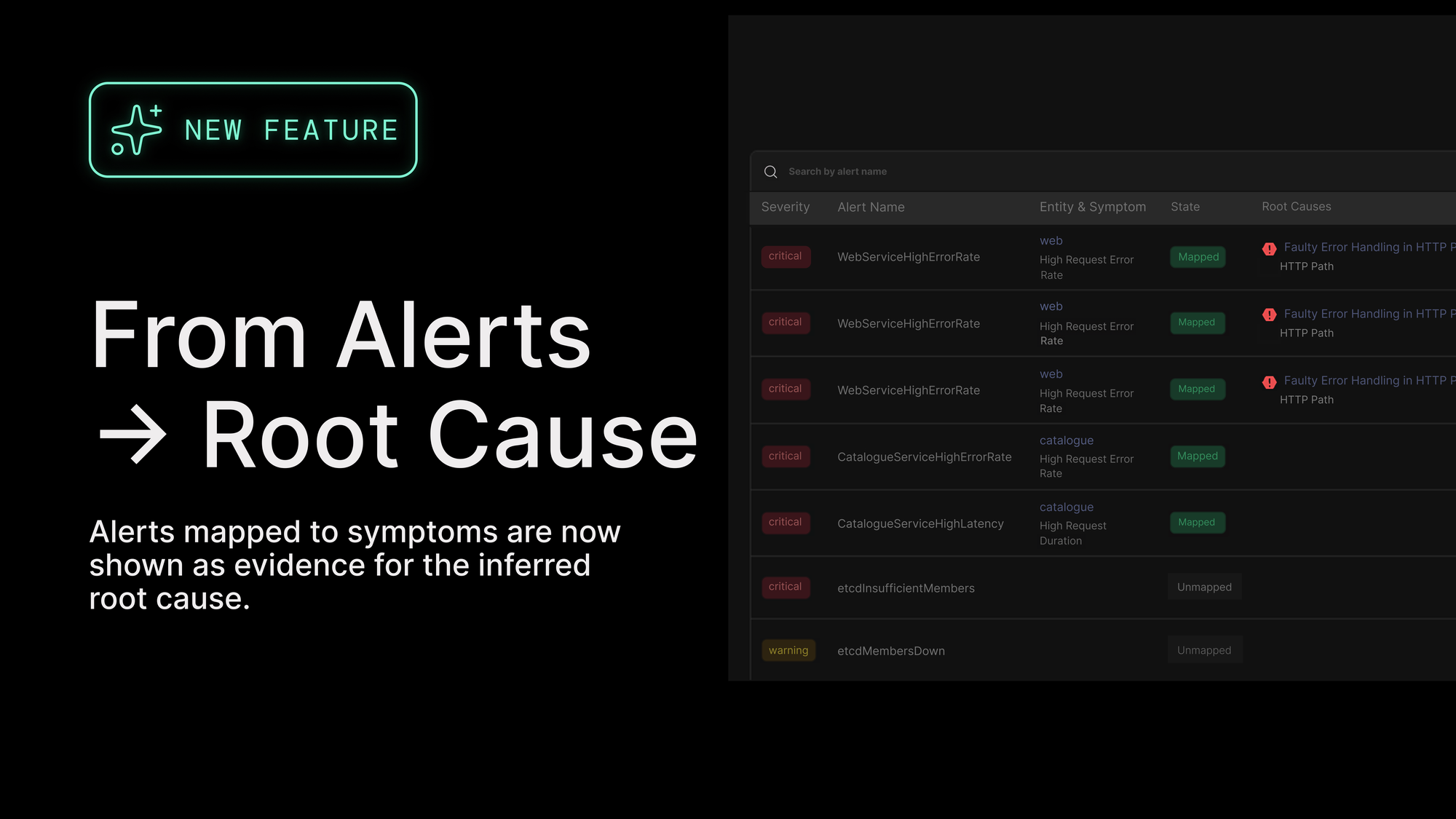

What changed in Causely

Our recent release adds the missing bridge.

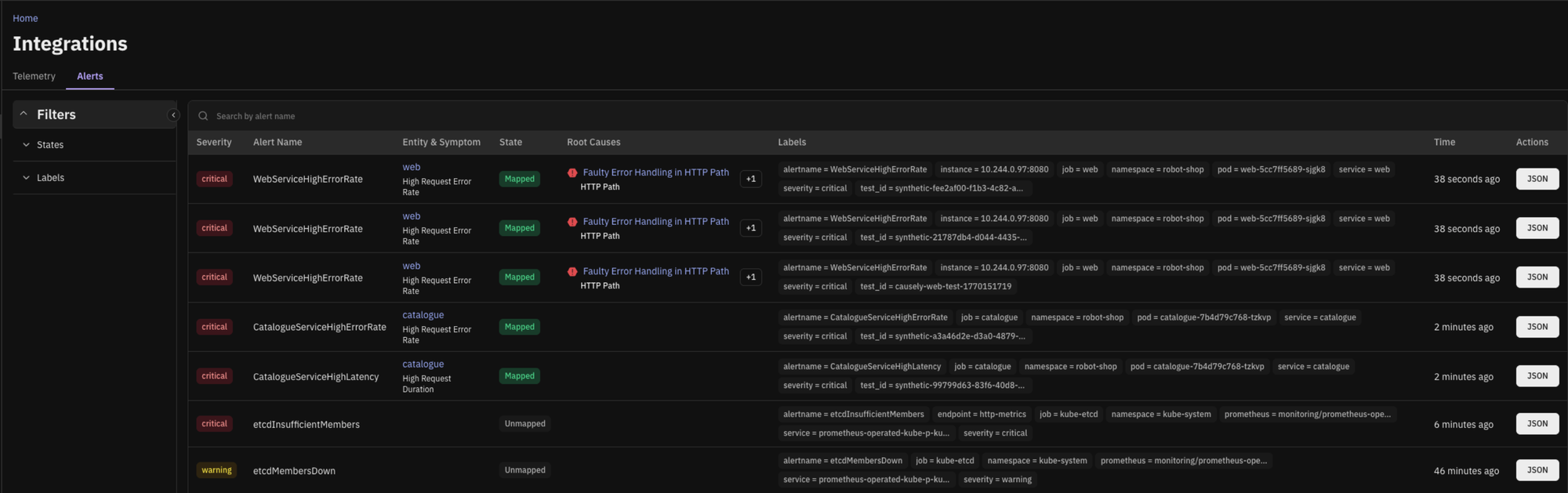

Causely already ingests alerts from tools teams rely on, including Alertmanager, Prometheus or Mimir, incident.io, and Datadog. What’s new is that the relationship between those alerts and Causely’s symptom and causal model is now explicit and visible.

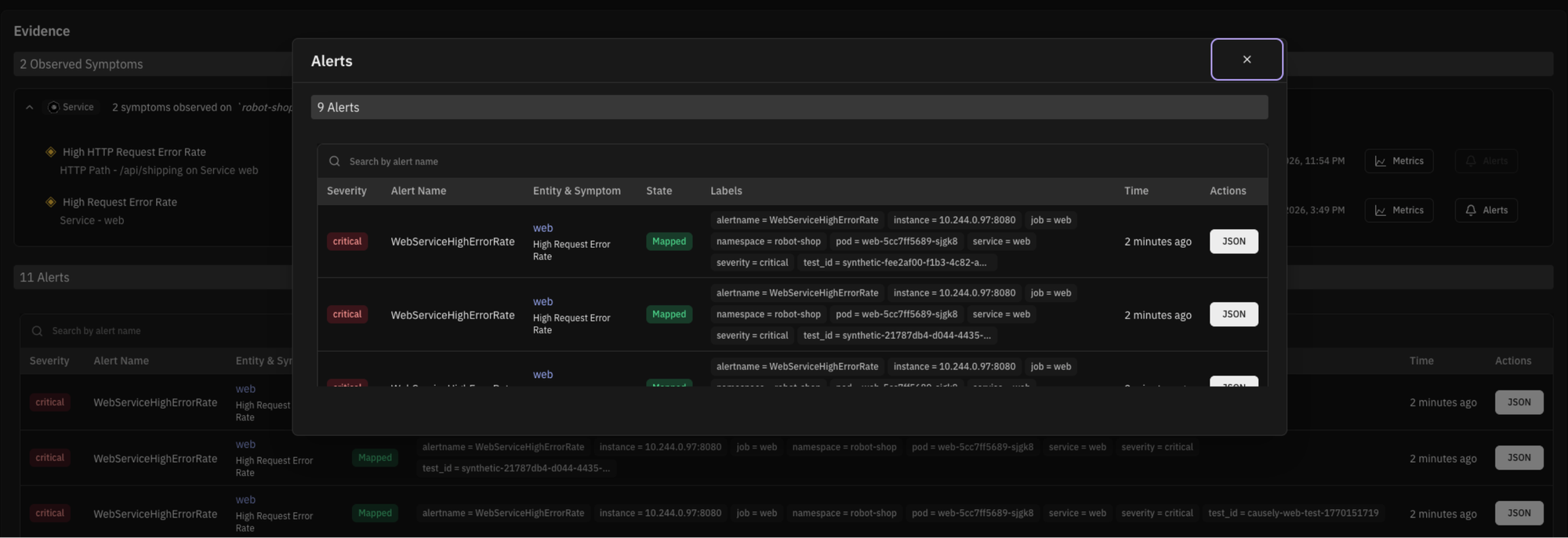

Each ingested alert is mapped to the symptom it represents and shown directly in the context of the inferred root cause.

Instead of treating alerts as separate problems, Causely treats them as evidence of system behavior. Multiple alerts that describe the same behavior collapse into a single symptom. Those symptoms are then connected through the causal model to the change, dependency, or resource actually driving the issue.

Alerts are no longer just timestamps and labels. They become part of a coherent system story.

You can also view alerts over time and see which symptoms and root causes they mapped to. This makes alert behavior visible and understandable, rather than noisy.

How this changes the first minutes of an incident

For the on-call engineer, the workflow changes immediately.

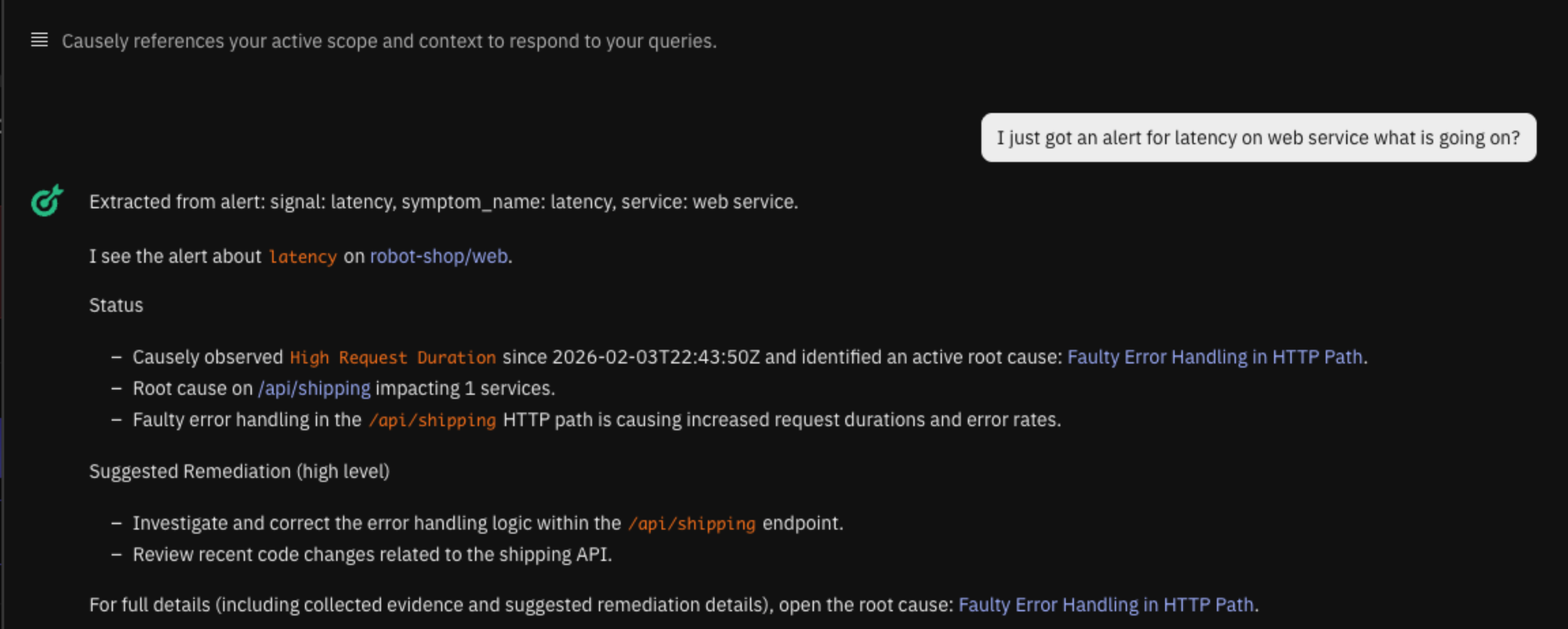

When a page fires, the alert can be pasted directly into Ask Causely. Instead of starting with dashboards, the engineer sees which symptom the alert maps to and whether there is an active root cause. The first question shifts from what to check to whether action is required now.

The same mapping is also available as structured context for automated workflows, so alerts no longer require manual interpretation to become actionable.

For teams dealing with alert noise, the change is cumulative. Over time, they can see which alerts consistently map to the same symptoms and causes. This builds trust that important behavior is covered and makes it easier to reason about which alerts are redundant versus genuinely distinct.

For reliability leads, gaps become visible. Alerts that do not map cleanly to existing symptoms stand out. Those gaps are no longer discovered mid-incident. They become clear opportunities to extend coverage where it actually matters.

From paging interface to investigation entry point

Alerts still wake people up. That does not change.

What changes is where investigation starts. Instead of beginning with translation and hypothesis building, teams start with an explanation that already accounts for how alerts relate to each other and to the system.

Over time, this shifts behavior. Engineers stop debating which alert is primary. War rooms converge faster on a shared narrative. Investigation energy moves from interpretation to containment. More importantly, alerts become explicit, interpretable signals that can drive response consistently, whether the next step is taken by a human or a system.

Causely does not replace alerting. It turns alerts into inputs to understanding.

Closing the gap

Alerts are not the investigation. They never were.

The cost teams pay today is not because they lack alerts or data, but because understanding arrives too late. By explicitly mapping alerts to symptoms and root causes, Causely closes the Page-to-Understanding Gap where most incidents stall, turning alerts from pages into grounded inputs for understanding and action.